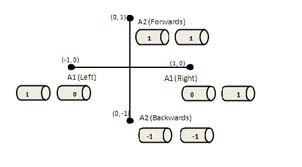

The joystick has two axes: let's call the horizontal axis A1 and the vertical axis A2 (see diagram). The program can read one input from each axis, so in the extreme case if the driver is pushing the joystick forward as far at it will go but not moving it side-to-side at all, the "coordinates" of that move are (0,1). Similarly, moving the joystick completely to the right but not forwards or backwards at all gets read as (1,0).

Now, of course all of this information has to get sent to the motors somehow. There is one motor on each axle of the robot, which we'll think of as the left motor and the right motor. In motor-land, the coordinates will be (left motor, right motor). We figured that in order for the robot to go forward, both motors need to spin forwards. In other words, (0,1) in joystick-land should correspond to (1,1) in motor-land (see diagram below). Similarly, (0, -1) in joystick-land means we want the robot to move backwards, so that would be

(-1,-1) in motor-land since both motors need to spin backwards. To make the robot turn to the right -- (1,0) in joystick land -- the right motor needs to spin forwards while the left motor remains still, so that would be (0,1) in motor-land. So you can see that it was really a matter of reading off the coordinates in joystick-land and transforming them over to coordinates in motor-land, as in the chart.

Knowing that a change of coordinates simply corresponds to a matrix transformation, we just had to figure out the matrix. That turns out to be really simple because of all the zeros and ones; for example, setting up one of the matrix equations:

tells us that b=1 and d=1. The others tell us that a=0 and c=1. So, we've figured out that when the program reads input from the joystick as (A1,A2), we want those coordinates to get multiplied by the matrix we found before getting sent to the motors. This means:

which tells us exactly what to do with the input from the joystick before sending it over to the motors!

I loved everything about this - the fact that transformations and matrices just "came up" when we were actually solving an interesting problem, the fact that I was able to explain this to the programmer on the robotics team (a 10th grader who had never seen matrices before), and the fact that the solution turns out to be so simple. What kills me is that I spent a month last year doing matrices with my 11th graders via some marginally interesting linear programming problem that didn't necessarily get at the essence of what matrices are. I know how I'll be teaching matrices in the future!

And now you will have a robot that they can see it on!

ReplyDeleteSome say I would teach robots all day if I could. They don't realize that in doing so, I am teaching Physics, Math, Engineering, Writing, Business, and Programming. Real world beats textbook any day in my opinion.

I especially love how you filled the whiteboard wall with matrices. The brainstorming is half the fun.

Thanks to you and the other "A" for all of your help this season.

This is really cool! I'm confused, however, about one thing. The transformation

ReplyDelete(0, 1) ---> (1, 1)

(1, 0) ---> (0, 1)

(0, -1) ---> (-1, -1)

(-1, 0) ---> (1, 0)

is not linear! If you call the transformation F, linearity would require that F(1, 0) = -F(-1, 0), and this condition is not satisfied: (0, 1) is not equal to -(1, 0).

Because the transformation isn't linear, it can't be carried out using pure matrix multiplication. That means the matrix formula you wrote down can't be doing what you want it to do.* And, indeed, it doesn't: if you multiply (-1, 0) by the matrix ((0, 1) (1, 1)), you get (0, -1), rather than (1, 0).

One possible fix is to use the transformation

(0, 1) ---> (1, 1)

(1, 0) ---> (-1, 1)

(0, -1) ---> (-1, -1)

(-1, 0) ---> (1, -1)

instead. This transformation is linear, and can therefore be carried out using matrix multiplication. It also gives the robot operator more flexibility, because it allows the left and right wheels to spin in opposite directions. Depending on how your wheel base is set up, this might allow for tighter turns.

* Incidentally, this is a nice example of how abstract ideas can be useful in practical situations: knowing a little something about abstract linear transformations makes it way easier to track down the bug in the robot control code. It might even lead you to notice the bug without even testing the code!